“Second nature” is a mindset, behavior or skill so ingrained by habit or practice that it seems natural or automatic, perhaps even lacking basis in conscious thought.

Second nature is most often associated with good habits, but in our age of hyper-media and rapidly changing technology, we can become so enmeshed in the promise of the better world that technology offers us, we fail to be critical of it.

Michael Gamble. Photo courtesy Michael Gamble.

Michael Gamble. Photo courtesy Michael Gamble.

Sustainability can be understood now as a sort of second nature, appearing everywhere – in buildings, on clothing, in our cars, toys, furniture, and devices. The term has trickled up and down the economic chain so as to appear on products from coal to cat food, and in some respects, is now a commodity rather than a concept that can spur meaningful action.

A key challenge for policy makers, engineers, and architects is to develop a fact based awareness of the role that sustainability has in shaping and directing technological development, and to take responsibility for it.

For example, the making of a landscape literally is an exercise in “second nature.” But when landscapes are conceived as purely picturesque or recreational, the environmental drawbacks can outweigh the benefits to a provisional public realm. We all see a park as inherently good. But if that park is designed without consideration of habitat, transportation or social equity, it can have a profoundly negative longterm impact.

Another example: plumbing. Removing wastewater in a sanitary way certainly solves a core problem related to public health and hygiene. But without a complete understanding of inputs, throughputs and outputs, we create other problems when we substitute the natural with a “second nature.” Until Atlanta’s recent (and ongoing) upgrade of our combined sewers, much of the city’s wastewater was dumped untreated after major rain events into rivers and creeks. In the process of solving neighborhood issues related to sanitation, another larger regional problem is created.

Deeply rooted principles of landscape and building design can conflict with stewardship of the natural and social environment. Our actions, if not grounded in proof through research, can have real consequences beyond the boundaries of any individual project.

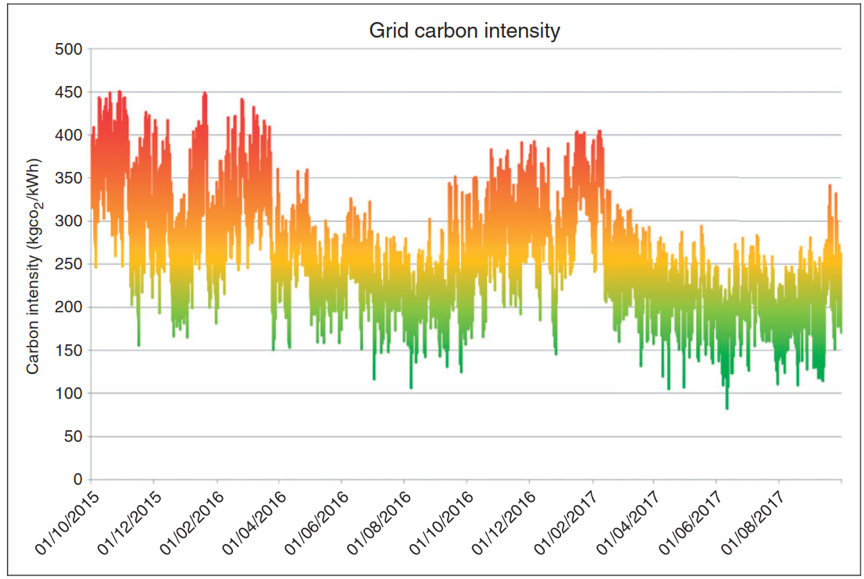

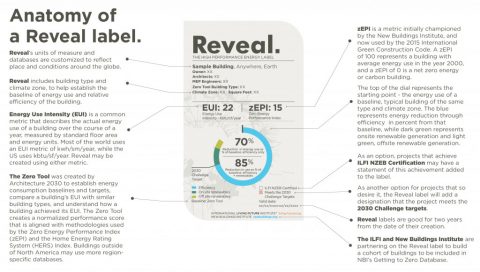

Tools to help with this task are emerging at the very time they’re needed. Energy and water modeling is helping project teams to evaluate the impacts of various options. Materials databases are finally on their way toward providing meaningful information about the impact of various products on nature. A pilot project funded by Georgia Tech’s Living Building Academic Council envisions using augmented and virtual reality interfaces to help identify design issues and to “crowdsource” solutions.

It may seem paradoxical that technology is so crucial to understanding what often seems to be the primitive disorder of nature. But the practice of creating the built environment remains a dynamic between instinct and analysis, creativity and technique, art and engineering.

We have to reach beyond the illusion of technology and technique, into a deeper systemic thinking about the impact of the second nature we create through the processes of designing and building. Sustainability can’t be placed on autopilot. Fact, effectiveness and innovation are the drivers that will truly advance the practice of sustainability and the creation of healthy, accessible and beautiful places.

Michael Gamble is the director of graduate studies at the Georgia Tech School of Architecture. He also chairs the Georgia Tech Living Building Academic Council. His column is part of our Building Thought Leaders series. If you’d like to republish or distribute this Building Thought Leaders column, please review these guidelines.