Jim Nicolow learned about the Just label soon after it was released in 2013. He immediately thought it would be a valuable tool for Lord Aeck Sargent.

As sustainability director and principal at the Atlanta architecture firm, Nicolow had been conscious of two recurring problems in the sustainable business movement: The “people leg” in the “three-legged stool” of “people, profit and planet” often is neglected. And companies that treat people well have few objective, quantifiable ways to show it. Just, Nicolow thought, provided a straight-forward, relatively simply way to address both challenges.

(Photo above: Lord Aeck Sargent offices in Atlanta. Image courtesy Lord Aeck Sargent; copyright by Jonathan Hillyer)

The label is described by the International Living Future Institute as “a voluntary disclosure tool for organizations.” It’s built around 22 broad “indicators,” with a primary focus on diversity, equity and benefits and other workplace issues.

Just also is tied to the Equity Petal within ILFI’s Living Building Challenge, which requires at least one member of an LBC project team to attain the label. That’s built some growth into the program. So far about 50 companies, nonprofits and public agencies have attained the label. In February, LAS became the 47th of them. The firm is one of four organizations involved in the Living Building project at Georgia Tech to hold a Just label (the others are the Epsten Group, The Miller Hull Partnership and the Southface Energy Institute).

To get a better idea of the Just process from a company’s perspective, I interviewed Nicolow on LAS’s experience. The answers have been edited for length and clarity.

What value did you see in pursuing Just? Is it a market differentiator that can help LAS compete on projects?

Just provides a way for us to express the strong sense of values that we share as a team. It’s not just that University X or Client Y is going to hire us because we have a Just label. That may happen. But the biggest argument for it is on the people side. … We’re a professional service firm, so our resources are the people themselves. In my own personal experience, you want to work for a firm that you believe in and that shares your values. And the most talented people are also the ones who are in the position to make the choice of where they work based on the values of that employer.

Jim Nicolow is sustainable director and a principal at Lord Aeck Sargent. Photo courtesy Lord Aeck Sargent.

Jim Nicolow is sustainable director and a principal at Lord Aeck Sargent. Photo courtesy Lord Aeck Sargent.

How did you go about pursuing the label?

We started to do kind of a gap analysis to see what it would take — much like you would when you’re trying to determine what level you should go for with green building rating system. You have to figure out what are the requirements, which ones you’ve already met, and what it would take to get there on the ones you haven’t met yet. So with Just, we had to ask: Do we have some of these policies in place already? And what would it take to get the other ones in place? … But everybody’s day jobs got in the way, and we didn’t push it that much further.

So you dropped pursuing Just until you became finalists on the Living Building project at Georgia Tech.

Yes. When we were shortlisted for the Living Building [in December 2015], I made it more of priority. The Living Building gave us a deadline. Starting back up on Just was pretty warmly embraced at the firm leadership level, because it lined up with our corporate values. There’s a very strong belief at LAS in treating employees well and in sustainability, and in the connection between those two things.

As an aside, can you clarify how sustainability and equity issues are connected?

Partly it’s just about doing the right thing. But we’re also seeing data now that shows that the firms that are embracing equity tend to perform better. The American Institute of Architects released a survey recently on the firms that won their Committee on the Environment Awards, going back several years. It was interesting to see that firms with a more balanced workforce tended to win the awards.

OK. So what did your gap analysis find?

Just is organized on a three-star system. You don’t need to get any of the stars to get the label, because it’s not a certification. It’s just a transparency tool. You could score zero across the board and still get a Just label. But nobody’s going to want to do that. Most of the indicators are organized in a similar fashion; you basically will get the first star if you have a policy in place for that category and demonstrate some basic level of performance. Our initial analysis found that we had seven policies in place, and we didn’t have policies for 14 of them [under an exemption allowance, LAS opted out of the “Animal Welfare” indicator]. But after that initial pass, we took a closer look, and found that we actually had policies for 12 of the categories. So there really was some value in just getting us to dig further to see for ourselves where we were.

So I assume you set to work getting more stars for each indicator?

The way we treated our initial label was almost like a baseline. Our goal was to get to two on all categories and to three stars on a lot of them. So the first thing we had to do was address the lack of even a policy on several of the indicators. So we drafted policies and got feedback from the employees. And then the leadership team adopted them.

Changing a bunch of firm-wide policies sounds time consuming.

It wasn’t difficult. Part of that is because [ILFI is] not asking us to do crazy stuff. It’s pretty basic. So for each of those, I put together a draft and ran it by senior leadership. None of them seemed like the kinds of thing we needed the entire board to vote on. I can imagine that if you were a more highly-structured organization there might be a more involved process.

Have you gotten a lot of pushback?

Not that much actually. And not really at all from the leadership. Where it’s come up is a handful of passionate staff, concerned about one or two areas where we can do better.

Beyond creating policies where you didn’t have them before, how did you move to two or three stars in so many areas?

We could have checked the box and say, ‘Yep, it’s met.’ But Just has a way of forcing you to look at policies in a comprehensive way that you wouldn’t do otherwise. If forced us to look at each of these indicators and to assess where we were. They fell into three categories: ‘Yeah, we clearly need to do more here.’ ‘No, we don’t need to.’ But most of them fell somewhere in the middle.’

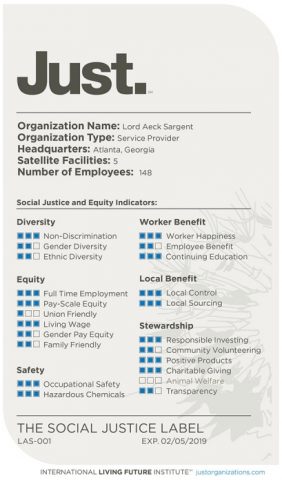

Lord Aeck Sargent’s Just label rates how the company treats its employees, among other values.

Lord Aeck Sargent’s Just label rates how the company treats its employees, among other values.

Who was doing all this?

We put together a task force, which is also analogous to the green building process, where you put together an integrated project team and look at things comprehensively. Of course, HR was involved, and also our operations people and leadership, and some people on the Living Building design team. I think that’s a strength of the program. You can’t do it in a vacuum. It forces you to invite different parts of the organization to sit at the table. If I were to look at lessons learned, I’d definitely recommend that you create a task force that brings in different parts of the organization, and that you bring leadership onboard early so that you have buy-in.

Were there some categories that prompted more discussion than others?

The Worker Happiness Indicator required a job satisfaction survey, and the staff filled that out and gave us very high ratings. But the most interesting part was that the survey also had a field for comments. There were a lot of ideas, such as providing resources for project managers and more support for professional development. We’re following up by trying to address these issues over the next year. That was sort of an unexpected outcome. The ones that probably prompted the most discussions at the time were the ones that involved benefits, like for example, paid family leave. We didn’t fully resolve that, but I do think ongoing discussions that were prompted by Just will eventually get us to where we want to be. The other one that prompted a lot of discussion at the time was gender pay equity.

Were some categories more challenging than others?

Gender Diversity and Gender Pay Equity are ongoing issues. Here I am — a white guy — so I sort of feel awkward being the one who challenges gender diversity or pay equity. You don’t know what you don’t know. But I asked two of my female leadership colleagues, ‘Can you take a look at this issue and see what you can make of this?’ And one of them is now on the compensation committee, which is where those decisions on pay are made, so that in itself is progress. That ongoing process has nothing to do with the label per se, other than that the label process prompted more discussion.

We don’t have parity in the leadership levels of the organization. There’s a generational thing happening. If you take it back to the schools, there are more women architecture students now. But 25 years ago, that wasn’t the case. So there’s a lag at getting into leadership positions. That doesn’t mean it’s OK. It just explains it. Another issue was the Ethnic Diversity Indicator. We feel like we’re very diverse compared to the industry. But you’re not compared to the industry; you’re compared to the local area, and Atlanta is a highly diverse community. So we got lower scores than we expected for Atlanta.

Have you moved farther on these issues since completing the Just process.

We’ve made the adjustments I noted regarding Gender Pay Equity, and we just formed a subcommittee of our Sustainability Forum that will focus on operational issues including the Just Label renewal.

How would you describe the scale of the Just process?

It took us a year. It could have been done in less time. One of the challenges with something like this is it’s nobody’s day job. And no one person has all these responsibilities. Members of the task force would work on one thing and maybe have to drop it, and then get back to it. It was not a terribly onerous effort. If I were to guess hours it might have been under 200.

Did you get the value you’d hoped for out of that effort?

I think it was tremendous return. The strength of a program like this is that it gives you something to measure yourself against. It takes something that is sort of esoteric and makes it specific. It also got people engaged and that’s always a challenging thing. I think we’ve also seen some positive press out of it. We’re talking about it when we’re recruiting. But to me the biggest benefit will be if it becomes an ongoing thing, where we look at it every two years and see if we can do better.