Jennifer Hirsch has lofty aspirations for the role that the Living Building at Georgia Tech could play in advancing social justice.

The Georgia Tech faculty member likens it to other parts of the Living Building Challenge. Energy must be net positive. So must water and waste.

“Then, how do we become net positive equity?” Hirsch asked the project’s Equity Petal Work Group during a May brainstorm.

The suggestion may strike some as fanciful. Can a building’s design, construction and ultimately its use play a truly meaningful role in addressing difficult societal problems? For that matter, what do issues like equal opportunity, diversity and fairness have to do with the built infrastructure?

Hirsch answers that making the connection isn’t as difficult as one might think.

“I’ve found that the professionals who are interested in green building are also the kinds of people who have a broader focus on the impact of their work,” she says. “They want their buildings to focus on quality of life and on what kinds of impact their buildings have on people.”

In theory, equity is a core principle of sustainable development. Sustainability consultants talk about a three-legged stool of “people, profit and planet” that is addressed most effectively when all three are addressed together. In practice, “people” issues have tended to take a back seat.

“The equity leg has often been overlooked,” says Kendeda Fund advisor Dennis Creech. “But green building is maturing. You can’t overlook the fact that how you design a building affects not just the health of the people who occupy it, but also the health of the people who manufacture the products in the building or who mine the materials. You can’t overlook how it affects people’s jobs and their opportunities.”

Jennifer Hirsch (second from right) leads a roundtable discussion at an Equity Petal Work Group charrette in May. Photo by Ken Edelstein.

Jennifer Hirsch (second from right) leads a roundtable discussion at an Equity Petal Work Group charrette in May. Photo by Ken Edelstein.

That presents the practical question of how a project can address issues like the ones Creech mentions. Architects are experts at the style, floor plan and materials of building. Engineers are good at modeling energy and designing mechanical systems. Typically though, nobody on the design team is trained to advance issues like justice, fairness and social responsibility.

The Living Building Challenge gets at some of those issues without explicitly labeling them as equity. Barring “red list” chemicals in a building can protect workers who might be exposed while manufacturing or installing a product. Buildings that stress walkability are taking a step toward healthier communities.

In 2009, LBC became the first green building standard to formally incorporate social and economic equity. LBC is built around seven broad categories, called “petals.” The Equity Petal’s overall goal is ambitious: “to transform developments to foster a true, inclusive sense of community.”

But the four requirements that fall under the Equity Petal, called “imperatives,” aren’t as far-reaching as they could be. One requires that half a percent of the project’s budget be given to an appropriate charity. Another imperative mandates walkable, “human scale” features. A third requires that the project protect public accessibility to air, water and nature. The fourth calls upon one organization involved in the project to obtain the International Living Future Institute Just label.

Even the Challenge’s champions acknowledge that the petal is a work in progress.

“We created the Equity Petal really as a marker in the ground to say we need to address equity in buildings,” says Amanda Sturgeon, CEO of the ILFI, which runs the Living Building Challenge. “It’s definitely something we hope will develop as part of an iterative process with our project teams.”

Equity Petal just the starting point

Design leaders on the Living Building at Georgia Tech are fairly confident about meeting the petal’s four imperatives. First of all, as a nonprofit governmental institution, the project is exempt from the charitable gift requirement. (According to Hirsch, the Equity Petal Work Group is encouraging Georgia Tech to contribute anyway.)

Secondly, like most buildings designed to Living Building standards, the plan already emphasizes human-scale features and access to nature. “For the most part,” lead architect Joshua Gassman of Lord Aeck Sargent says, “the things you would do to fulfill those imperatives could easily be categorized simply as good design ethos.”

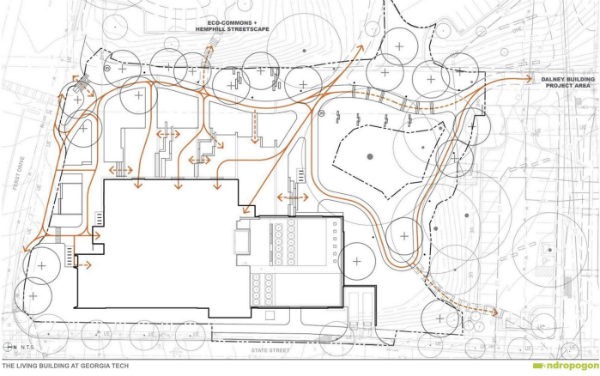

Gassman does note one exception: The Equity Petal requires Living Buildings to design for “universal access” — a higher standard than compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. As a result, paths outside the building follow a more gradual slope than the ADA requires, and, as the first floor slopes down, interior ramps play a more prominent role than stairs do.

Then, there’s the “Just” label. Just is an ILFI initiative intended to “help your organization optimize policies that improve social equity and enhance employee engagement.” It’s a voluntary disclosure tool that focuses primarily on workplace policies. Before work began on Georgia Tech’s Living Building, The Miller Hull Partnership of Seattle (which is partnering with LAS as architects on the building) and the Southface Energy Institute (which is serving as a consultant) had earned its Just label. That was more than enough to meet the imperative. But now the requirement has been exceeded because Lord Aeck Sargent and the Epsten Group (another consultant) also have obtained the label.

Some circulation routes are longer to create a gentler grade than required under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Image by Andropogon.

Some circulation routes are longer to create a gentler grade than required under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Image by Andropogon.

Georgia Tech’s own personnel are working to exceed the Equity Petal in other areas. Chris Burke, the university’s community relations director, says that’s driven by the fact that Georgia Tech is a state institution with global reach. Its mission includes “improving the human condition in Georgia, the United States, and around the globe.”

“We’re looking at this building to pilot some larger goals — to test and highlight improvements in the way we do things that could work elsewhere on campus,” says Chris Burke, Georgia Tech’s director of community relations.

Drew Cutright, who’s managing Georgia Tech’s efforts to leverage the impact of the Living Building and chairs the Equity Petal Work Group along with Hirsch, has a more a basic explanation for the way Tech staff and faculty have embraced the petal.

“Equity is such a complex subject, and it’s difficult to find opportunities to address it,” Cutright says. “A lot of folks in a university community like a challenge. And this is a challenge.”

Ambitious and intricate

Work Group members have laid out an ambitious agenda. They want to involve underrepresented campus groups as well as off-campus community members in the building’s design, operations and programs. They’re working with Skanska, the lead contractor, to figure out ways to train and hire nearby residents for construction jobs. They want to “create a welcoming building culture,” to make the building into a “living learning lab” on equity, and to find ways to measure the effectiveness of their equity efforts.

Hirsch frames the overall task this way: “How can a building build community? How does a building create [and] encourage human action that’s going to help people build a better world?”

That’s a daunting challenge, particularly given the lack of a well-worn path toward advancing equity in building projects. But Hirsch’s background seems appropriate to the task. She’s a cultural anthropologist who consulted for various organizations on equity, sustainability and the built environment before joining the Georgia Tech faculty in 2015 to lead its new Center for Serve-Learn-Sustain. SLS is a campus-wide initiative that aims to equip “students with the knowledge and capabilities to effectively address sustainability challenges and inter-related community-level societal needs.”

Every few weeks, it seems, she’s leading roundtables where more participants spin out fresh ideas and try to figure out how to implement them. One such meeting, in early June, attracted Georgia Tech students, a Lord Aeck Sargent architect and even Emory University’s director of sustainability initiatives. It provided a venue for the kind of intricate idea-making that’s part of weaving equity and environmental solutions together.

Ciannat Howett, the Emory sustainability chief, offered up a suggestion based on her own experience: How about scheduling custodians in the new building to work days rather than nights?

“By moving to daytime custodial pickups, you’re creating relationships because the students run into the person who’s cleaning up, and they get to know them,” Howett said. “When students start understanding that person’s job, they end up creating less waste.”

Hirsch notes that conversations about such modest topics can evolve toward much deeper issues, such as the role non-faculty employees may play in student development and the fairness of the pay structure.

Even big ideas about equity tend to require intricate problem solving. Cutright, who’s trained as an environmental planner, is currently working through the issues involved in making the building more welcoming to the non-Tech community. One aspect of that challenge is campus access: Can paths better connect nearby neighborhoods to the Living Building on campus?

Another aspect has to do with operations: How can the Georgia Tech Police Department balance welcoming diverse outsiders with security?

And finally there’s programming in the building itself.

“It’s not just the physical issue of the building. It’s also how it’s used,” Cutright says. “Creating a set of shared values around the Living Building Challenge requires creating experiences that engage multiple audiences.”

For Cutright, both the building and the activities inside and around it will determine whether the project has a meaningful impact on equity.

“I find the idea of making the building welcoming to people from different walks of life fascinating,” Cutright says. How do you create a community around a building?”