The Southeast’s only fully certified Living Building has been singled out for special recognition among this year’s AIA COTE Top Ten Award winners.

The AIA Committee for the The Environment cited the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Brock Environmental Center as the sole “Top Ten Plus” building for its “exceptional post-occupancy performance.” It’s part of a new initiative for the 21-year-old awards program to begin considering actual — not just predicted — environmental performance.

Also among the 10 recognized projects were the Kern Center at Hampshire College, which was completed last year to meet Living Building Challenge standards, and Discovery Elementary School, which we featured last month as a prime example of a net zero school.

COTE bills its Top Ten Awards as “the industry’s premier program celebrating sustainable design excellence.” For 2017, the committee employed a rigorous scoring system that stresses performance metrics as much as it does design. The recognition comes in advance of Earth Day and a few days after AIA issued a statement expressing the profession’s sense of urgency about the role buildings can play in combatting climate change.

Here’s a quick look at the three winning projects that particularly interested us, with a few notes on the lessons each may hold for other deep-green buildings. (Below, you’ll find briefer descriptions and links to the seven other award winners).

Brock Environmental Center

Students visit the Brock Environmental Center to learn about Chesapeake Bay’s ecology and also how buildings can help to restore the environment. Brock images by Prakash Patel/courtesy SmithGroup JJR.

Students visit the Brock Environmental Center to learn about Chesapeake Bay’s ecology and also how buildings can help to restore the environment. Brock images by Prakash Patel/courtesy SmithGroup JJR.

Owner: Chesapeake Bay Foundation

Architects: SmithGroup JJR

Project site: greenfield

Building program types: education, office and public assembly

In 2001, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation opened the world’s first LEED Platinum building, the Philip Merrill Environmental Center in Annapolis, Md. Fifteen years later, the Foundation’s Brock Environmental Center attained its own sustainability landmark: It became the first fully certified Living Building Challenge project in the Southeast.

Like the Merrill Center, the Brock Center was designed by the Washington, D.C., office of SmithGroup JJR. It serves as a hub for the foundation’s educational and restoration operations at the southern end of the 200-mile long bay.

A porch roof along Brock Environmental Center’s southern face is one of the building’s passive features.

A porch roof along Brock Environmental Center’s southern face is one of the building’s passive features.

The building, which sits right next to the bay, was designed to express the foundation’s mission: to collaborate with other organizations, agencies and people to protect the bay, a threatened resource whose watershed spans five states and the District of Columbia. According to information submitted by the design team to COTE, the Foundation “aspired to manifest true sustainability, creating a landmark that transcends notions of ‘doing less harm’ towards a reality where architecture can create a positive, regenerative impact on both the environment and society.”

As the only certified Living Building Challenge project among this year’s Top Ten, the Brock Center also was recognized with a “Top Ten Plus” honor for its “exceptional post-occupancy performance.” Under LBC 2.0, the 10,518-square-foot building was required to attain net-zero energy, waste and water. It met those goals with flying colors: Projected to reach an astoundingly low energy unity intensity of 15.5, the building performed from April 2015 to April 2016 at an EUI of 14.12. Its wind turbines and solar panels generated 80 percent more energy than the building used.

Clerestory windows to the north (left) provide light and ventilation for southerly winds while clerestories to the south ventilate northerly winds.

Clerestory windows to the north (left) provide light and ventilation for southerly winds while clerestories to the south ventilate northerly winds.

Intensive passive features and a sophisticated variety of HVAC equipment — including variable refrigerant flow units, a dedicated outside air system and 18 ground-source wells — helped achieve that exceptional performance, according to materials the project team sent to COTE:

The Center’s form and orientation maximize opportunities for daylighting and natural ventilation. The long bar curves slightly to the east, allowing morning sun to preheat the interior. An optimized exterior envelope (R-31 walls, R-50 roof, R-7 windows) significantly reduces heating demand. Carefully-placed and frugally-sized windows (25 percent window-to-wall ratio) provide optimal daylight, views, and ventilation, without excessive heat gain.

A porch lines the south façade sheltering the interior from unwanted heat gain, while large, north-facing clerestory windows provide glare-free daylight. There are no west-facing windows. Open, loft-like interiors promote natural stack/cross ventilation.

Recalling vernacular architecture of the Southeast, Brock’s floor plate is interrupted by a “dogtrot”—an open air pass-through that creates a comfortable micro-climate, while promoting airflow to reduce horizontal stratification. A VRF HVAC system coupled with dedicated outside air ventilation, utilizes 18 ground-source wells, improving heating and cooling efficiency. Occupancy/vacancy sensors control lighting, ventilation, and plugs (reducing “vampire” loads).

As for design, the building’s distinctive curved roofs evoke ocean waves, windswept dunes, even clamshells, while the roof’s zinc shingles sparkle in sunlight like fish scales. Other features, including the dogtrot and a system of pier-like ramps that lead up to the main floor root the building in its locality. Many of those features also happen to meet environmental imperatives: Water resistant cypress siding was harvested from nearby “sinker logs.” The ramp was necessary to elevate the building to protect from storm surges, which are projected to reach higher because of climste change. And that curved roof to the west minimizes heat gain from the afternoon sun.

Find out more at:

R.W. Kern Center at Hampshire College

The R.W. Kern Center at Hampshire College is an entry point for new students. It anchors a more pedestrian-oriented quad. Image courtesy Bruner/Cott.

The R.W. Kern Center at Hampshire College is an entry point for new students. It anchors a more pedestrian-oriented quad. Image courtesy Bruner/Cott.

Location: Amherst, Mass.

Owner: Hampshire College

Architect: Bruner/Cott & Associates

Project site: brownfield

Building program type: higher education

The 17,000-square-foot Kern Center was built to Living Building Challenge standards. It opened last fall and could be fully certified later this year.

The project was driven by an institutional commitment to sustainability. Hampshire College’s goal is for the entire campus to be carbon neutral by 2020. The Kern Center is both a very prominent emblem of that commitment and major step toward getting there. So it’s not surprising that the building embraces the opportunity to educate visitors by featuring exposed cisterns, conduit, ducts and piping, as well as a prominently displaying an building dashboard in the commons area.

Exposed materials and systems greet visitors at the Kern Center, which embraces the idea of educating visitors about green buildings. Image courtesy Bruner/Cott.

Exposed materials and systems greet visitors at the Kern Center, which embraces the idea of educating visitors about green buildings. Image courtesy Bruner/Cott.

Much like the Living Building at Georgia Tech (a primary focus of our Living Building Chronicle), Kern is a multi-purpose campus facility. It includes the small liberal arts college’s admissions and financial-aid offices, as well as classrooms, a gallery and a small cafe. Those multiple uses also create challenges regarding climate zones and the kinds of systems necessary to condition each of them.

The well-insulated building is projected to perform at an EUI of 23 — very impressive in the cold New England climate — and to produce at least as much clean energy and water as it uses. According to the submission to COTE:

The doublestud cavity wall and roof are filled with cellulose to achieve assembly values of R-40 and R-60, respectively. Tall operable windows help achieve a fully daylight building with a window to wall ratio of 30 percent. An inverter-driven heat pump system provides heating and cooling to the spaces, separate from the heat recovery ventilation system.

Interestingly, Kern’s rooftop PV system is tied to a campus grid that eventually will be include a larger solar array with storage capacity, which will be independent of the regional grid.

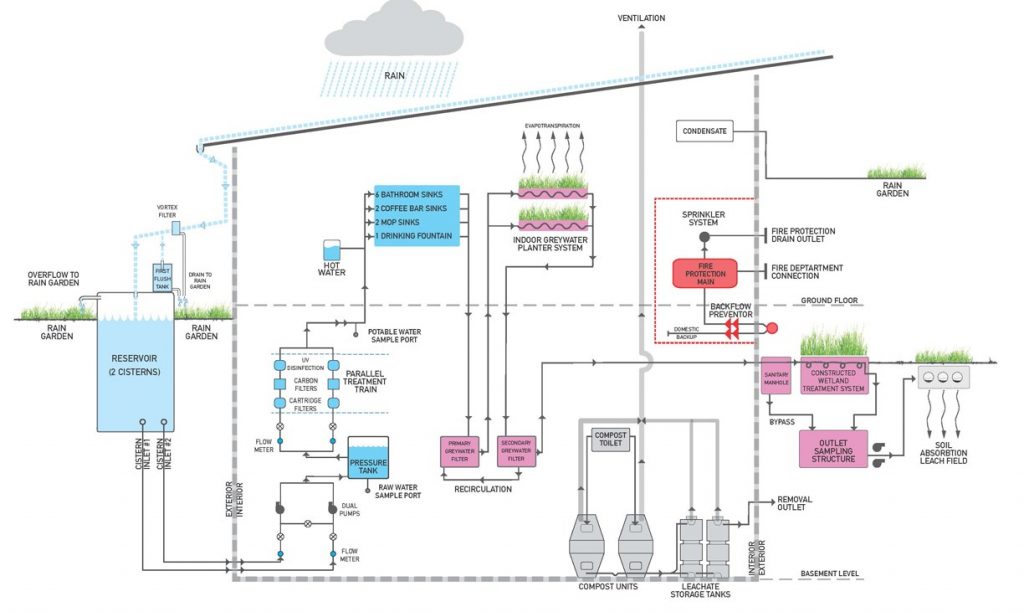

The Kern Center is designed to achieve net zero water with compost toilets, indoor greywater planters and constructed wetlands. Image courtesy Bruner/Cott.

The Kern Center is designed to achieve net zero water with compost toilets, indoor greywater planters and constructed wetlands. Image courtesy Bruner/Cott.

Like other LBC project teams, the Kern Center design team reported that being limited to local, sustainable and nontoxic materials presented an enormous challenge, which in turn spurred creative solutions. The team’s solutions involved simplifying materials palette “to eliminate troublesome finishes and plastics.” So local stone and local timber were used. Both of those nature materials also help to connect the building to its rolling, mountainous site.

Find out more at:

Discovery Elementary School

Discovery Elementary School is terraced into a south-facing slope, which allows site lines to mask a rooftop solar array. Photo by Lincoln Barbour Photography.

Discovery Elementary School is terraced into a south-facing slope, which allows site lines to mask a rooftop solar array. Photo by Lincoln Barbour Photography.

Location: Arlington, Va.

Owner: Arlington Public Schools

Architects: VMDO Architects

Project site: previously developed land

Building program type: K-12 School

Discovery Elementary School is one of the nation’s largest net zero energy buildings. It also incorporates native plants, rainwater storage, abundant daylighting, locally sourced stone and insulated concretes forms.

But the school may be more notable in the way that it carries its sustainable theme over to students and teachers. Both the interior and the exterior incorporate sustainable themes — at times in a playful way intended to create “a place students couldn’t wait to get to in the morning and didn’t want to leave in the afternoon.” Themes for each grade are based on natural realms, ranging from the backyard to the galaxy. An oculus opening through the awning at the entrance creates a solar calendar. A huge energy-performance digital dashboard graces the lobby. As the design team told the COTE judges:

Two important design process criteria were paramount: challenge the tendency of low expectations, and focus on children first. The resulting primary design goal was to provide a joyful and engaging environment for learning–a place students couldn’t wait to get to in the morning and didn’t want to leave in the afternoon. The secondary goal was to design a building that would not just use less resources, but make a regenerative contribution to the well-being of its occupants, site and the world at large—specifically regarding the crisis of climate change.

That creativity carries over to other aspects of the building: A slide allows students to get from the second to the first floor. Kindergartners can hang out in colorful cubby holes that have become popular even among older kids. More significantly, faced with neighborhood opposition to visible solar panels on top of the school, VMDO terraced the building into its south-sloping site, which had the effect of making it less easy to see the panels.

Playful design elements evoke environmental themes throughout Discovery Elementary School. Photo by Lincoln Barbour Photography

Playful design elements evoke environmental themes throughout Discovery Elementary School. Photo by Lincoln Barbour Photography

According to VMDO, the school’s impact is rippling outward: “The design team was asked to consult on significant modifications to a prototype design for a local jurisdiction, and they have just opened what should be the first net zero school in Maryland. Arlington Public Schools is now asking for net zero energy for all their new schools, and the A/E team is currently designing a larger net zero school on a more constrained site. Wanting to keep up with the school system, the County has now started design on a net zero community center.”

Find out more at:

• AIA

Seven more COTE winners

Here are AIA’s descriptions of the seven other buildings honored among the COTE Top Ten. Follow the links to more details on these projects.

Bristol Community College John J. Sbrega Health and Science Building, Fall River Mass., Sasaki: Bristol set ambitious goals of making its new science building not only elegant and inviting, but also a model of sustainability. The 50,000-square-foot building sets the standard as the first ZNE academic science building in the Northeast. Providing hands-on learning opportunities and care to underserved populations, its program accommodates instructional labs and support space for field biology, biotech, microbiology, and chemistry; nursing simulation labs; clinical laboratory science and medical assisting labs; dental hygiene labs; and a teaching clinic. Taking a holistic approach to the design and construction of the Sbrega Health and Science Building, the team uncovered innovative ways to eliminate the use of fossil fuels, increase efficiency, and dramatically reduce demand.

Chatham University Eden Hall Campus, Richland Township, Pa., Mithun: After receiving the donation of 388-acre Eden Hall Farm north of Pittsburgh, Chatham University conceived an audacious goal to create the world’s first net-positive campus. Home of the Falk School of Sustainability, Eden Hall Campus generates more energy than it uses, is a water resource, produces food, recycles nutrients, and supports habitat and healthy soils while developing the next generation of environmental stewards. Linked buildings, landscapes and infrastructure support an active and experiential research environment. New building forms, outdoor gathering spaces and integrated artwork complement and interpret natural site systems, while making cutting-edge sustainable strategies transparent and explicit.

Manhattan Districts 1/2/5 Garage & Spring Street Salt Shed: New York City, Dattner Architects and WXY architecture + urban design: The Garage and Salt Shed celebrate the role of civic infrastructure by integrating innovative architectural design with sustainability and a sensitivity to the urban context. The building is wrapped in a custom perforated double-skin façade that reduces solar gain while allowing daylight and views in personnel areas. The 1.5 acre extensive green roof reduces heat-island effect, promotes biodiversity, and filters waste steam condensate and rainwater allowing it to be reused for truck wash. The projects are also benchmarks for NYC’s Active Design program, which promotes the health and fitness of occupants through building design.

Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, Washington, D.C., Payette and Ayers Saint Gross: The Milken Institute School of Public Health at GWU embeds core public health values — movement, light/air, greenery, connection to place, social interaction, community engagement — in a highly unconventional, LEED Platinum building on an urban campus in the heart of the nation’s capital. Research offices, classrooms and study areas are clustered around an array of multi-floor void spaces that open the building’s dense core to daylight and views. An irresistible, sky-lit stair ascends all eight levels, encouraging physical activity. The pod-like classrooms are set in from the perimeter so informal study and social interaction space can overlook the bustling traffic circle.

Ng Teng Fong General Hospital & Jurong Community Hospital, Singapore, HOK, USA; CPG, Singapore; Studio 505, Australia: The Green Mark Platinum NTFGH is part of Singapore’s first medical campus to combine continuing care from outpatient to post-acute care. Based on passive principles, the performance-based design supports resource efficiency, health, and well-being. Seventy percent of the facility is naturally ventilated, representing 82% of inpatient beds. Unlike its Singaporean peers, NTFGH provides every patient with an adjacent operable window, offering daylight and views. An oasis in a dense city, NTFGH incorporates parks, green roofs and vertical plantings throughout the campus. The building uses 38% less energy than a typical Singaporean hospital and 69% less than a typical U.S. hospital.

NOAA Daniel K. Inouye Regional Center, Honolulu, HOK with Ferraro Choi & WSP: Located on a national historic landmark site on Oahu’s Ford Island, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Inouye Regional Center features the adaptive reuse of two World War II-era airplane hangars linked by a new steel and glass building. The hangars inspired beautifully simple design solutions for how the center uses air, water and light. The LEED Gold complex accommodates 800 people in a research and office facility that integrates NOAA’s mission of “science, service and stewardship” with Hawaii’s cultural traditions and ecology. The interior environment, which is based on principles of campus design, creates a central gathering place.

Stanford University Central Energy Facility, Stanford, Calif. ZGF Architects LLP: At the heart of Stanford University’s transformational, campus-wide energy system is a new, technologically advanced central energy facility. The system replaces a 100% fossil-fuel-based co-generation plant with primarily electrical power—65% of which comes from renewable sources—and a first-of-its-kind heat recovery system, significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and fossil fuel and water use. The facility comprises a net-positive-energy administrative building, a heat recovery chiller plant, a cooling and heating plant, a service yard, and a new campus-wide main electrical substation. Designed to sensitively integrate into the surrounding campus, the architectural expression is one of lightness, transparency and sustainability to express the facility’s purpose.